Beyond Good Intentions

Written by: Theunis Duminy

Date: 2025-03-25

PhilosophyDecision MakingEthics

My heart's in the right place, right?

"We judge ourselves by our intentions and others by their behavior." - Stephen Covey

Everyone and their mother has read How to Win Friends and Influence People. For good reason, it's an excellent, timeless book. But the particular story of Francis "Two Gun" Crowley from the first chapter has always stuck with me.

Crowley killed at least two people in cold blood—a police officer and a person who resisted his robbery attempt. He helped a friend dispose of a woman's body who refused the friend's romantic advances. Patently clear, a human bereft of good will.

Here is an excerpt from How to Win Friends and Influence People of the day he was arrested:

One hundred and fifty police officers and detectives laid siege to his top-floor hideaway. They chopped holes in the roof; they tried to smoke out Crowley, the “cop killer,” with tear gas. Then they mounted their machine guns on surrounding buildings, and for more than an hour one of New York's fine residential areas reverberated with the crack of pistol fire and the rat-tat-tat of machine guns. Crowley, crouching behind an overstuffed chair, fired incessantly at the police. Ten thousand excited people watched the battle. Nothing like it had ever before been seen on the sidewalks of New York.

Crowley wrote a letter in the middle of this siege. This letter, stained crimson with his blood, said: "To whom it may concern. Under my coat is a weary heart, but a kind one—one that would do nobody any harm."

This bewildered me. He killed people, yet seemed convinced his actions were justified. He thought himself a good person. As he arrived on the day of his execution by electric chair, he was heard to have said "This is what I get for defending myself."

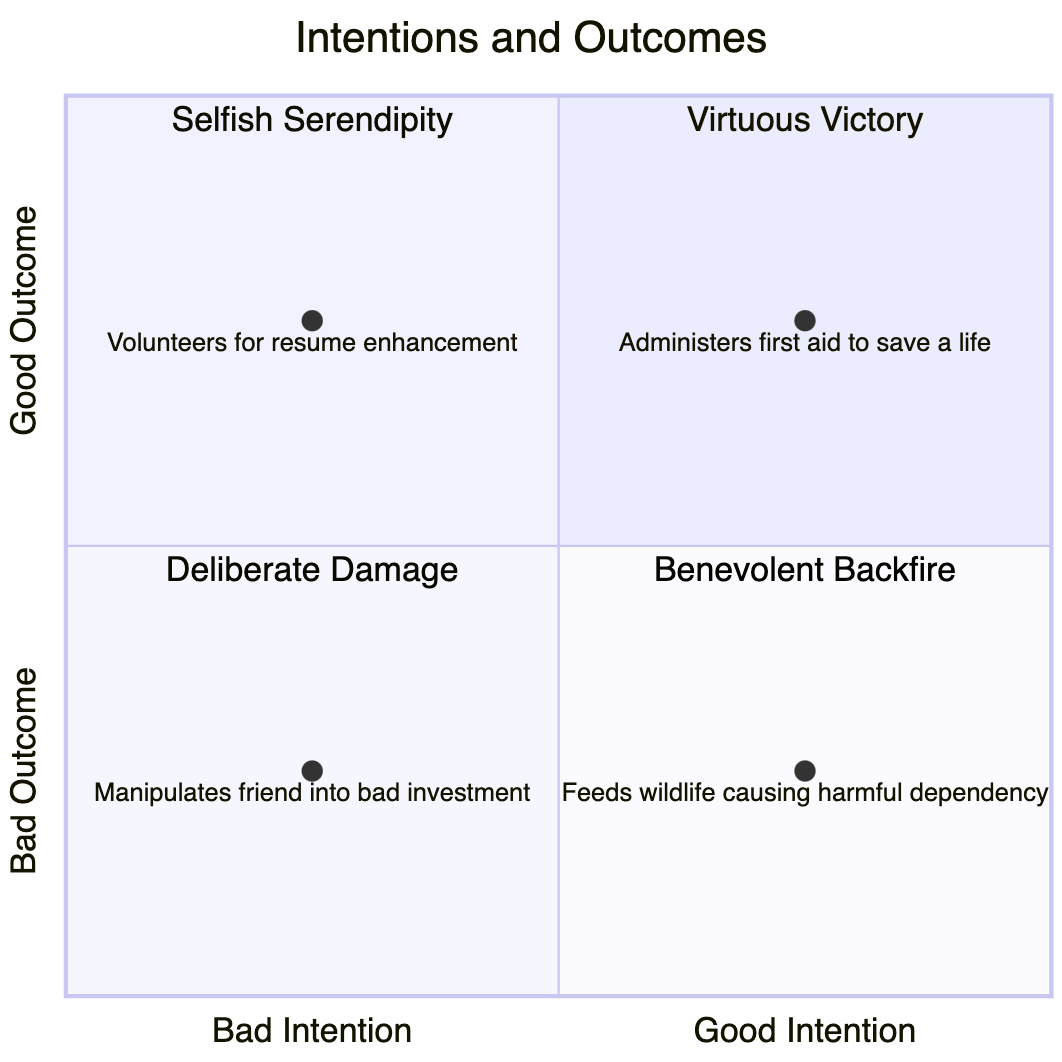

The takeaway seems clear: People can justify their actions—beyond all rationality—as necessary, fair and correct. As a result of Crowley's story, a belief was fixed in me that intention should not matter. What should matter, the only factor of importance, is the outcome of an action.

Unintentionally changing my mind

"The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in the mind at the same time, and still retain the ability to function." - F. Scott Fitzgerald

I wanted to write about that belief with strong conviction. When I started writing I was confident I would be able to convincingly argue that intention shouldn't matter and, in fact, the consequence of an action is the determining factor of moral worth. What a fool I was!

Writing is interesting in that it reveals the understanding of your own beliefs. It's more loose, holding an idea in your mind, than ordering words in a way to lucidly describe it. To my surprise, the more I wrote, thought and researched the piece, the more nuanced the answer became.

See, the thing is, there are obvious scenarios where intention does matter. Murders are differentiated from manslaughter—for good reason. We instinctively understand why a nuance should exist based on the intention. This example shows why we care about intentions to begin with.

We care because nobody can fully predict the outcome of an action and all the subsequent, cascading dominoes that might fall. Ergo, we try and determine whether a person was making the right decision with the information they had. Did they mean well, we ask.

Wait a minute, the devil's advocate says. We've all seen people take credit for good outcomes, regardless of their intention. But when something turns out bad or harmful we'll hear "Sorry, that wasn't my intention". It's obviously disingenuous, yet we struggle to prove intention inasmuch as we can prove someone has a headache. Intentions and headaches, it turns out, have a lot in common. It's very easy to fake having them.

When noticing this double standard, taking credit when things go well but dodging blame when they don't, I cannot help but be reminded of Charlie Munger's famous quote: "Show me the incentive and I'll show you the outcome." Maybe looking at what motivates people tells us more about their actions than what they claim their intentions were. When we keep hiding behind "good intentions" even though we're causing harm, we probably need to take a hard look at what's really driving us. Are we after social approval? Trying to avoid confrontation? Just wanting to see ourselves as good people? These incentives often operate below the level of conscious intention.

The vexing thing about witnessing the intentions spiel is that it's too easy a cop out. We know when we're lying about having a headache but we have this peculiar quality of being able to convince ourselves of our own good intentions. Humans are drawn to avoid responsibility for their actions. They will go to extraordinary feats of mental gymnastics to convince themselves and others of their good heart—like Crowley.

Exactly that tendency, or temptation, of avoiding responsibility is why I find an intention-first-consequences-second mindset so nefarious. It's the perfect discouragement for taking responsibility, because regardless of what happened, or the damage, we can just say our intentions were good. If we're able to retrospectively rationalise our actions as being well-intended, then we never have to confront the fact that sometimes we cause bad things to happen. Even if we didn't mean to. It conveniently absolves us of the responsibility to be better.

I've come to understand what I think the root of the problem is: every person has their own way to measure what counts as good intentions. It becomes flexible and deeply subjective depending on the situation at hand and, naturally, how many people are paying attention. If this is true, the solution seems easy enough. Find a way to measure intentions fairly, and objectively. One of those "easy in theory hard in practice" solutions. There cannot be a way to empiricise every person's subjective reality—or could there?

We might be in luck.

Debating consequences versus intentions is not new. An enormously influential thinker, Immanuel Kant, had a strong opinion about the primacy of intention, and, his work has always had a huge influence on my thinking. He strongly opposed consequentialism. Yet, I never made the obvious connection between my own strongly held consequentialist beliefs and the tension they create with Kant's philosophy, which I admire so much.

Kantian ethics

"Science is organised knowledge. Wisdom is organised life." - Immanuel Kant

Immanuel Kant was a 18th-century German philosopher—a key Enlightenment thinker. Often called the father of modern philosophy, Kant developed a moral framework that had a profound impact on our understanding of ethics and human rights.

That's because Kant took morality pretty seriously. He was particularly serious about two things: the intrinsic value of human beings and the importance of rationality in moral decision-making. While his work is dense, and intimidating (did I mention he was German?), his central ideas are both profound and approachable when broken down.

Kant believed that morality is rooted in intentions rather than consequences. What makes an action morally good, he argued, isn't its outcome but the will behind it—what he called a "good will." A good will means acting out of a sense of moral duty for its own sake, not because of personal gain or the potential consequences.

Kant recognised that not all obligations are the same. Some depend on what you want to achieve, while others apply universally, no matter your desires or circumstances. He divided these into two types of commands: hypothetical imperatives, which are conditional, and categorical imperatives, which are absolute. So, in short:

- Hypothetical imperatives tell you what to do if you want to achieve a specific goal. For example, "If you want to get fit, you should exercise." These only apply if you care about the goal; if you don't want to get fit, you have no obligation to exercise.

- Categorical imperatives, on the other hand, are moral rules that apply universally. They must be followed regardless of your personal goals or desires because they represent what is intrinsically right.

This Categorical Imperative is Kant's most famous contribution to moral philosophy, and is expressed in four formulations. Even though I could spend hours talking about each individually, I'd like to focus on one specifically. For your sanity, and mine.

The formulation we're spotlighting is called the Principle of Universalisability and it provides a method for evaluating whether an action or intention is morally right. If the principle cannot be applied consistently to everyone to behave the same, then it fails the test of morality.

Universalisability

"Act only according to that maxim whereby you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law without contradiction" - Immanuel Kant

Admittedly a mouthful. Despite the syllable density, on further exploration, it fits quite naturally and seems almost obvious. Before you take any action, simply ask yourself, "What's the maxim of my action?". The maxim merely refers to the rule or principle of that action. It's best explained with an example, one that Kant himself used.

Imagine someone needs money badly. They want to borrow it, but they know they can't pay it back. They also know that nobody will lend them money unless they promise to repay it. This person struggles with their conscience and wonders, "Is it okay to promise something I know I can't deliver just to solve my problem?"

If they decide to go ahead, their reasoning could be summarised as: "When I need money, I'll promise to repay it even though I know I won't."

Now, let's test if this reasoning works universally. What if everyone acted like this? If everyone made promises they didn't intend to keep, promises would stop having any value. No one would believe anyone's promises, and the whole system of borrowing money would collapse.

Therefore, this way of thinking fails because it couldn't work as a universal rule for everyone to follow. The very idea of a promise would lose its meaning. That makes it morally wrong to act this way.

To bring this into our modern context, consider social media. Someone might think, "I'll share this dramatic news story without verifying it because it fits my worldview." But if everyone followed this maxim, our information ecosystem would collapse (which is busy happening) into unreliability. The universalisability test reveals that such behaviour fails the moral test, regardless of intent.

You can apply this to any situation where there would be a moral expectation for anybody to act similarly. This takes away the subjectivity of the individual to apply their own justification because they are forced to ask if they'd be happy if everyone acted in that manner, even when they're on the receiving end.

Idealism: Where pragmatism goes to die

"Idealism increases in direct proportion to one's distance from the problem." - John Galsworthy

Kant's philosophy was criticised, as all great thinkers are, on the rigidity of his moral framework and often the impracticality of it in more complex, real-world situations. These criticisms don't diminish Kant's towering influence. His philosophy reshaped metaphysics, epistemology, and ethics. It's also fair to say critics often reflected their own philosophical agenda.

However, I cannot help but agree that the Categorical Imperative is idealistic. The honest truth is that it puts too much faith in human reasoning. You don't have to spend too much time in the real world to realise that reason is an uncommon grace.

Most of the time people are operating on autopilot. They're not impartial moral philosophers; they're survival-oriented creatures with an extraordinary capacity for self-deception. Kant's moral philosophy might be too good for the earth it inhabits, the ears it falls on.

This gap between philosophical ideals and reality is precisely where we struggle most. Consider workplace conflicts, family disputes, or social media arguments—all places where we readily attribute noble intentions to ourselves while judging others harshly for their actions. This asymmetry isn't just unfair; it actively impedes our growth. When we shield ourselves with the armour of "good intentions," we never fully confront the impacts of our choices.

Ours is an ethical tightrope predicated on acknowledging the messiness. Intention cannot be a static mental state internalised and wielded when it suits us. Rather, it's demonstrated through patterns. They are revealed not in your words, but in your actions. Above all, they are revealed when they lead to harm. When we are faced with a choice—rationalise or repent—the reaction to reach for intention, I fear, is a clear sign of our own moral demise.

Final thoughts

"The road to hell is paved with good intentions." - Proverb

Returning to Crowley's bloodstained note, I'm struck by our desperation to believe in our own goodness. Kant strongly affirmed the intrinsic value of human beings and their capacity to achieve goodness through rational moral action. His philosophy resonates deeply with me because of this immense potential he saw.

What we can take, then, is that although his is a rigid code, it shows that intention cannot be measured in our subjective reality. It's not our lived experience, as we so frequently hear, that matters, but whether we would be happy for everyone to behave according to the maxims we choose.

In the end, the most moral stance might be to judge our own actions mainly by their consequences while giving others the benefit of the doubt regarding their intentions. This demands accountability from ourselves, a humble acknowledgment of impact, while extending grace to others—not because this is philosophically perfect, but because it's the approach most likely to foster both personal growth and social harmony in our imperfect world.

For most of us, unlike Crowley, our hearts are in the right place. I genuinely believe most people want to do good, but it's in bridging the gap between idealism and pragmatism that ultimately matters.

All this to say that beyond our good intentions lies the work to prove the placement of our hearts. The true measure of a person is the grace we allow others that is not afforded to ourselves. Our worth, the burden we choose to carry, can only be measured by the good we create in this world.

Thanks to Mignon Duminy and James Rothmann for reading drafts of this.

Back to all notes