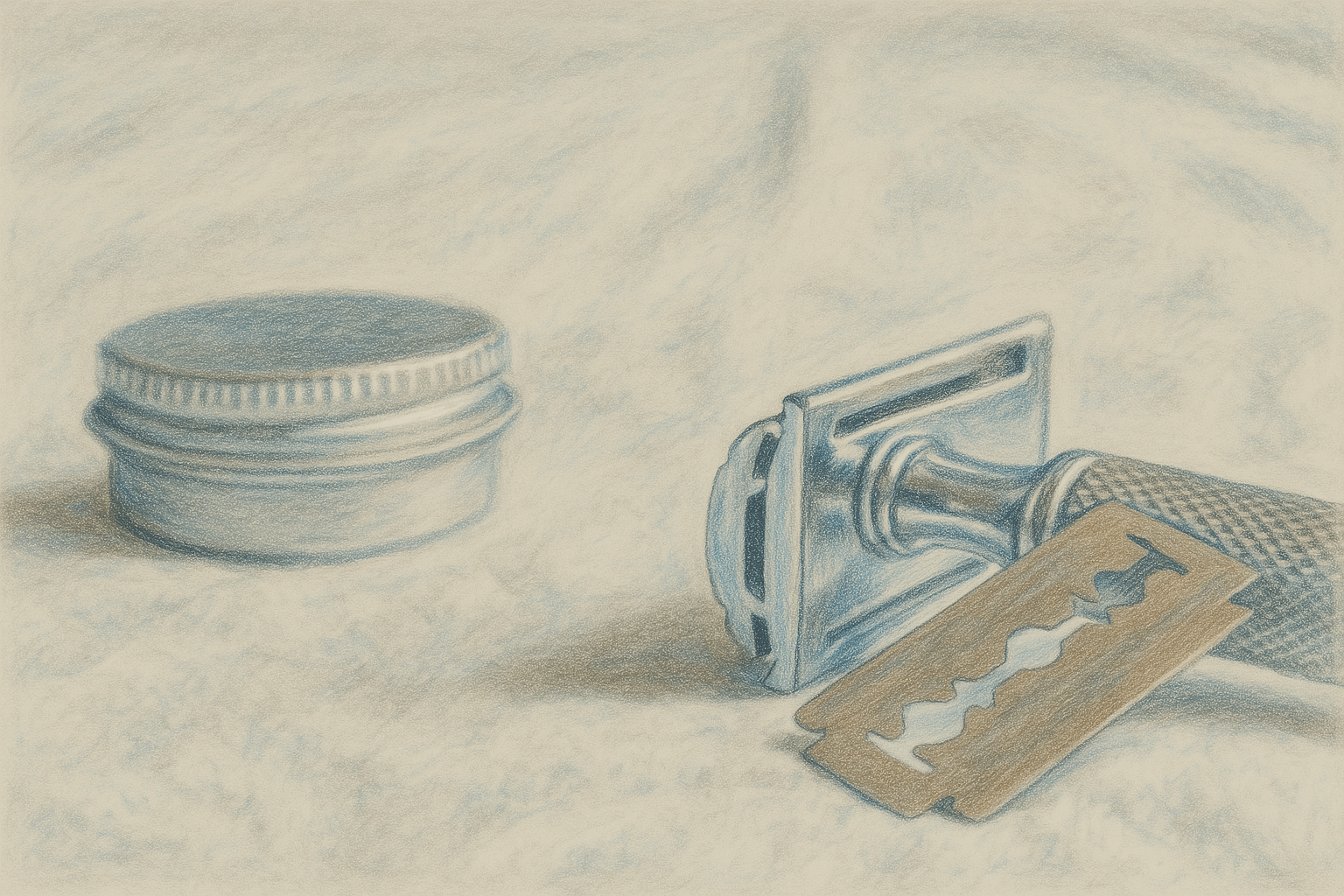

Shaving Our Thinking with Philosophical Razors

Written by: Theunis Duminy

Date: 2024-11-04

PhilosophyDecision MakingMental Models

Philosophical what now?

Great decision-making is a rare skill. It's difficult to get it consistently right. Luckily, mental models can help us habituate critical thinking. But, great mental models require great thinking tools. To that end, I'd like to explore philosophical razors and their ability to serve as decision-making tools.

Philosophical razors originate from prominent thinkers and philosophers as tools used to guide their decision-making process. Think of them as mental shortcuts that help simplify complex problems. They eliminate (shave off, get it?) unlikely explanations.

The tricky part is that these are not foolproof rules that guarantee flawless decision-making. In reality, they're just another set of tools that increases the likelihood of making good decisions.

This isn't an exhaustive list of razors, but I've found these to be the most pragmatic ones. We’ll dive into each razor—what it is, how to use it in real-world decisions, and where it might fall short.

Philosophical Razors (that I like)

Occam's Razor

"Entities should not be multiplied beyond necessity." — William of Ockham

TL;DR: Simplify solutions by minimising assumptions.

Often misunderstood to suggest that the simplest solution is always the best, Occam's Razor asserts that when multiple explanations are possible, start with the one with the fewest assumptions.

When your computer is acting up, the tongue-in-cheek advice is, "Have you tried turning it off and on again?" Usually, this works! While you could look for hardware issues or worry about a virus, it's often best to start with the solution that requires the fewest assumptions.

Sometimes, the simplest solution isn't the correct one. I like to use this as a rule of thumb to decide which solution to start with when I have multiple solutions that I am confident could be correct.

Hanlon's Razor

"Never attribute to malice that which can be adequately explained by stupidity." — Robert J. Hanlon

TL;DR: People do stupid things that seem malicious because of ignorance.

We seldom judge ourselves as harshly as we do others. Our knee-jerk reaction is to assume malicious intent in other people when their actions affect us negatively. This razor encourages us to assume people might simply be ignorant or careless rather than malicious.

It's a powerful tool to create a less hostile worldview. When someone doesn't reply to your message, instead of spiralling that they dislike you or are upset, assume they might just be busy. When a colleague misses a deadline or skips a meeting, which is more likely: They have an elaborate scheme to undermine you, or they are bad at managing their time?

Unfortunately, there are times when people do act with malicious intent. A word to the wise—stay cautious and remember the age-old adage: "Fool me once, shame on you; fool me twice, shame on me."

Hitchens's Razor

"What can be asserted without evidence can also be dismissed without evidence." — Christopher Hitchens

TL;DR: Dismiss arguments presented without evidence.

The burden of proof lies entirely with the person making the claim. Critics of an unsubstantiated claim are not obligated to disprove it, and you should not waste time trying to debunk arguments clearly untrue. In fact, many obviously false claims gains prominence in our discourse simply because people try to disprove the inherently non-falsifiable.

If someone claims they can predict lottery numbers without any proof, you are under no obligation to consider their claim until they provide evidence. Similarly, while some believe we live in a simulation—a fun idea to discuss—it cannot be taken seriously as it’s neither provable nor disprovable.

This should not entice us to prematurely dismiss ideas that have merit but lacks immediate evidence. All new ideas, the best ones, often seem the most outlandish on face value. We must balance being open-minded but sceptical to allow evidence to emerge.

The Sagan Standard

Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence. — Carl Sagan

TL;DR: In God we trust, all others must bring data.

A close friend to Hitchens' Razor, the Sagan Standard states the essence of the scientific method. I like to think of this as the personalisation of Hitchens' Razor. If you want to convince people of your claim, you need the data to prove it.

It's reasonable to trust me when I say the name of my dog is Suzy, but if I claim to communicate telepathically with Suzy, I need to provide substantial evidence (which I have ample of, by the way).

An extraordinary idea isn't false merely for being extraordinary. Finding novelty often means stepping into the unknown. It becomes our responsibility to turn the unknown into the measurable, and expecting the same of others who wants to be believed.

Hume's razor

"If the cause, assigned for any effect, be not sufficient to produce it, we must either reject that cause, or add to it such qualities as will give it a just proportion to the effect." – David Hume

TL;DR: Correlation does not imply causation.

Humans love to draw conclusions. We are hard wired to try and connect the dots that led to an event. Convincing ourselves the world makes sense helps us sleep better at night. The problem is, we often draw the wrong conclusions.

Not to be confused with Hume's law, which deals with the is-ought problem, this razor deals with the plausibility of causation. It's best explained with an example. A psychologist notes a rise in anxiety amongst teenagers and attributes it solely to social media usage. Is this sufficient? What about other causes, like increased academic pressure or economic uncertainty? If the cause can't sufficiently explain the phenomenon, we need to either reject it or modify accordingly.

The limitation is clear. It's exceedingly rare that an event has a single, clear cause, and not all causes fit neatly into empirical observation. Therefore, we should approach multi-casual issues with caution when applying this razor to ensure we don't dismiss them prematurely.

Grice's Razor

"Conversational implications are to be preferred over semantic context for linguistic explanations." — H. P. Grice

TL;DR: Focus on intended meaning rather than literal semantics in conversation.

In conversations, try to understand what someone intends to say rather than the literal meaning of their words. Few things are as teeth-grindingly frustrating like arguments over semantics. We rarely appreciate how hard it to articulate thoughts clearly. Universally, and ironically, people genuinely want to be heard.

"You never help around the house" they say. Of course, they do not literally mean never. However, they do feel unsupported at that moment. Instead of arguing about the term never, address their feelings and concerns. I promise the conversation will go better.

To reiterate, thoughts are hard to express clearly, especially when heightened with emotions. Ask questions to help people express themselves more clearly. Intent isn't always easily to discern, so don't assume you can read minds. Ask questions.

Newton's Flaming Laser Sword

"That which cannot be settled by experiment is not worth debating." — Alder'z razor

TL;DR: Debate only what can be settled by experiment; disregard the rest.

Also knows as Adler's razor, which he called "much sharper and more dangerous than Occam's razor". Adler was a sharp critic of the influence of Greek philosophy in modern philosophy.

He used the example of the irresistible force paradox: What happens when an irresistible force is exerted on an immovable object? According to this razor, the premise is flawed. Either the object is moved (thus making it movable), or it isn't (thus the force is resistible).

An example I like is debating endlessly whether a new business idea will succeed. Instead of talking, launch an MVP to test its viability in the real world.

But before we start feeling smarter than Greek philosophers, not everything worth discussing can be tested directly. Ethical and philosophical questions require debate and often cannot be settled with experiment. Abstract ideas and novel thinking plays a big role in the cohesion of societies.

Final thoughts

The difficulty of weighing all of these razors in our mind is striking to me. Some can outright contradict each other. Therein lies the beauty, in the eye of the beholder—or in this case, with the person holding the razor. You need to apply judgement when to use them.

Undoubtedly, these philosophical razors are powerful tools that can improve decision-making. We can apply these principles to create mental models that help us cut through complexities.

Remember, razors are not definitive methods for determining right from wrong. They are guiding principles and nothing more. Use them wisely to navigate through the noise. I've mostly written this as a way to understand these better, I hope you do too.

Lastly, not everything is empirical and clear-cut. It would be pretty boring if it were. Being human means wrestling with the abstract. Do not let these deter you from exploring novel ideas. As Einstein was thought to have said: "Not everything that can be counted, counts. And not everything that counts, can be counted."

Thanks to Mignon Duminy for reading drafts of this.

Back to all notes