The Doorknob Principle

Written by: Theunis Duminy

Date: 2025-08-24

Decision MakingEthics

My grandparents had a beautiful house on the coast where my mother's side of the family would get together for Christmas. Childhood memories tend to be sparse, but I remember how much I loved being in that house.

We ran on the perfectly cut grass, the cousins, keeping ourselves entertained long enough to have more of the delectable cake our grandmother made for us. There was a wooden crate filled with toys and balls to keep us busy. We tried not to, but inevitably a plant would become the victim of a well-struck football. It was the best time.

With the passing years, as I grew taller, I noticed a design quirk in the house. I had to bend over to open doors. Every doorknob was lower than you'd expect, just over half a metre from the ground. Bending to open a door was a tiny inconvenience so it never made sense to ask why it was that way. It was simply an accepted oddity of the house. Something you'd notice and forget about shortly after.

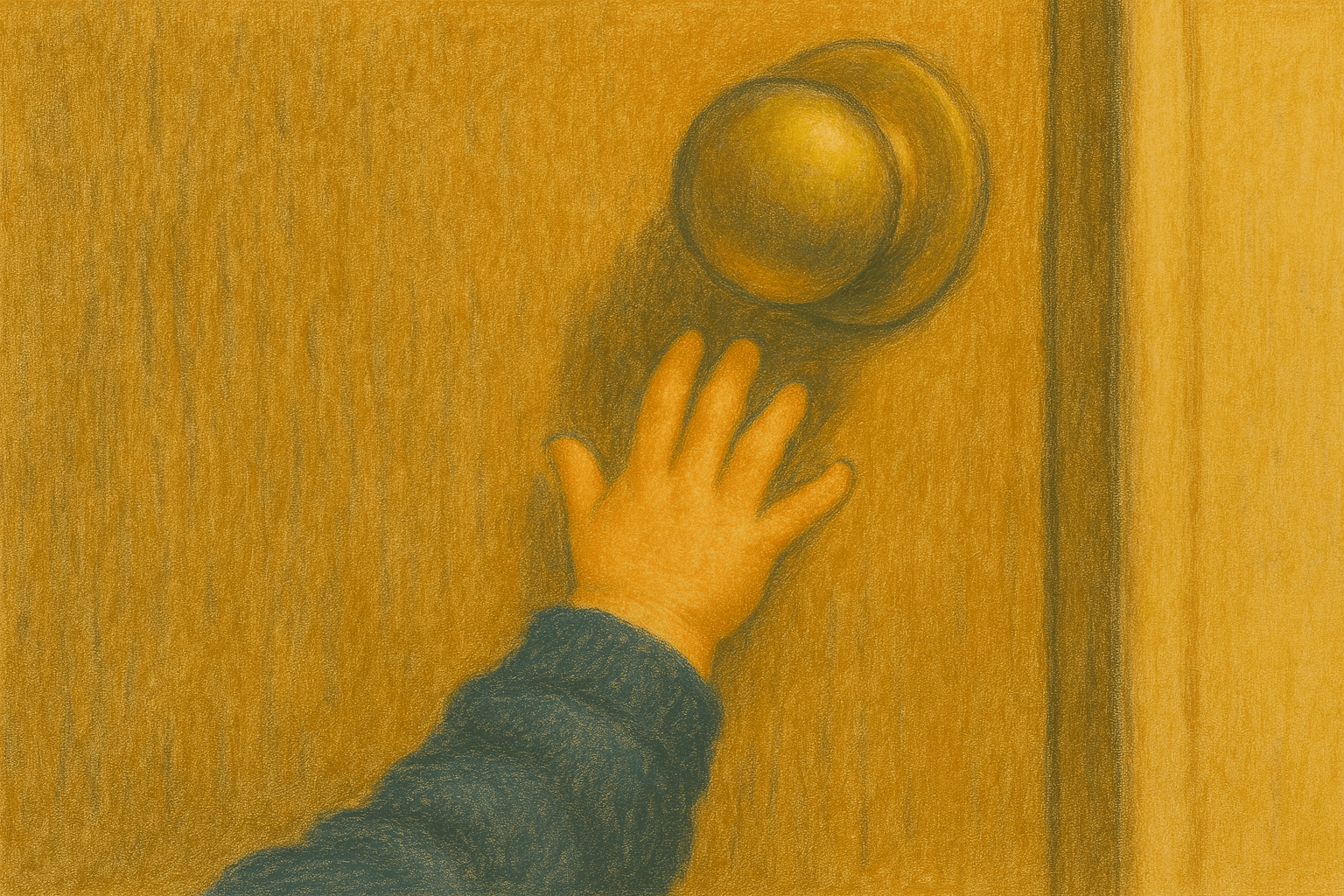

One December, I finally understood why it was built that way. I saw my sister, much younger and shorter than me, reach up only slightly to open a door. Aha! If the doorknobs were higher, she wouldn't have been able to open any doors. The accessibility for children came at the minor hindrance of reaching down for adults.

That doorknob taught me something about accessible design. But the real lesson came years later, when I was planning dinner with friends and one was seriously allergic to shellfish. I caught myself thinking: Everyone else could happily skip the shrimp, but she couldn't choose to ignore her allergy. Suddenly I was in that house again, watching my sister reach for the doorknob. Our decisions shape what's possible for other people.

I think about the placement of that doorknob often. The principle extends far beyond architecture, and shows up constantly. Every day, we decide where to place the doorknob for others to come in. I've come to lovingly refer to it as the Doorknob Principle. It goes like this:

Bend towards the person who can't reach towards you.

See, the thing with that doorknob is that it was never about adults sacrificing convenience for the sake of the children. No, it was about recognising inherent asymmetric capabilities and designing accordingly. Adults can bend down; children cannot reach up. The doorknob's height was an acknowledgement of reality.

You'll see this asymmetrical constraint everywhere, especially in relationships. Have you ever been in any of these situations?

- You can take leave anytime, they have specific holiday periods

- You're happy with double dates or group dinners, they're anxious in large groups

- You're fine with aisle or window seats, they get claustrophobic in middle seats

Unaware of the Doorknob Principle, we might frame the solution as only two options: What outcome makes me the happiest, or what outcome makes them the happiest. The issue with this framing is that it creates a zero-sum game where someone is getting the short end of the stick. But that's rarely the case. Decisions have more optionality than we often see at first, and that's what this principle helps us recognise.

Rather than competing over what each person wants most, we can focus on what neither can accept. Eliminate those options first. In the doorknob example, that means avoiding placements the child can't reach or that require excessive bending for the adults. It's also not as simple as finding a middle ground. We are searching for what works for the person who can't adapt, provided it doesn't cause genuine hardship for the person who can.

Importantly, this is not advocating for appeasing others at your own expense. Sometimes decisions aren't as binary as "we both love this" or "we both hate this". Often you're simply indifferent to an outcome that would help the other person. That being said, we must avoid both selfish comfort and pointless martyrdom. Don't choose ease at their expense, but don't choose suffering at your own.

The beauty of the Doorknob Principle is that it's not rooted in pity or altruism. It's clear-eyed design that acknowledges capabilities aren't fixed. The child grows taller, the adult grows older and less flexible. In relationships, we alternate between having options and needing them. The person who requires accommodation shifts with changing circumstances and seasons of life. The principle simply helps us see who has the greater capacity to adapt in any given moment.

The Doorknob Principle expects growth. It's an investment in reciprocity. When I started high school, I needed others to lower the doorknob for me by explaining unspoken rules, traditions, and social hierarchies invisible to an outsider. The older students could easily share what was second nature to them, but I couldn't magically know what took years to learn. However, the principle expects that in time I'd grow into that knowledge and become the one explaining things to the new kids.

But the principle also reveals something else: Those who refuse to grow. In healthy relationships, we alternate between bending and being accommodated. We all know people who always need you to plan around their schedule, preferences, and constraints, but when you need flexibility, there's never any bending in return. The principle exposes them as children who refuse to grow.

I never asked my grandparents why they built it that way. I'd like to think that during their planning, they saw a kid struggle with a door and made a choice. Whether intentional or not, they were teaching us that a thoughtful decision isn't sacrifice, but our way of making room for everyone to come inside. One day, they thought, our grandchildren will watch their own kids easily open those doors and realise the small act of bending was, in fact, never a hindrance. It's love, architected.

Thanks to Mignon Duminy for reading drafts of this.

Back to all notes